The whole world knows about the ogre that haunts creative people, the monster known as Creativity Block. Even people who have never written a story or a poem, even people who've never picked up a brush or a pencil know about the dreaded Block. You'll be glad to know that we don't need a super hero to pulverize this nemesis into Creativity Block Powder. We can defeat this enemy ourselves. Yes, we can. I know what I'm talking about because I did it, and once I developed a new way of thinking and working, I never saw The Block again. It didn't happen overnight, of course. It took a lot of self-examination to get rid of the pesky thing.

It's important to understand the ammo required to destroy the Block. What worked for me was a lot of self-examination. You see we each construct The Block in our own creative way. That's right, you may hear echos of other voices in The Block, but its power comes from your belief in it. For some people the block may be a wall of bricks (individual self-negating, judgmental messages neatly cemented together). For others it is a stone monolith of voices and experiences, fears, and self-doubt. No one builds The Block for you, and no one can take it down for you.

In the next few blogs I'd like to dissect The Block, and let others see what worked for me. I hope that through my teaching, writing, and coaching I have helped other people dismantle their blocks. This blog is one more place where I can hope to do some good.

Looking back on my own battle with The Block, I recognize that an important contributing factor was a paradox of expectations. In order for me to really value what I was creating I had to see that it was exceptional. I had absorbed that ridiculous myth about great artists being discovered like Lana Turner sipping a soda in Schrafts. Believe me, if you have that "star is born" I'm-gonna-be-discovered mythology in your head, wash it out now. The world recognizes Pablo Picasso was an artistic genius, the artistic giant of the twentieth century, but Pablo did not come out of the womb wielding a paint brush, instead he was taught from infancy about art by his father who was not only an artist but an art teacher. He surrounded little Pablo with the finest art and instruction from the time he could hold a crayon. In fact, the boy skipped normal child forms of expression and spent his lifetime trying to attain it. The same was true of Frank Lloyd Wright probably the greatest architect of his time. His parent's groomed him to be an architect, selecting the creative tools for that profession and surrounding their son with them.

Most of us were not so fortunate. Trying to value your work by comparisons to those giants is only going to add mortar to the Block's blocks. Wanting to be famous as an artist or in any field is not a serious creative goal, it is an ego trip. Living a creative life isn't about fame or recognition of any kind, it is an adventure of the spirit and the intellect engaged with the world, its creatures, animate and inanimate.

Someone once said of Picasso after observing him looking at a painting, "It's a wonder there was anything left on the canvas." His eyes were voracious consumers of the world around him. And that is first weapon in the destruction of The Block: a passionate hunger to see the world around you. Seeing becomes so important that drawings become authentic recordings of that seeing. Here is the key: the experience of seeing becomes more powerful and important than the product. This helps the artist disconnect from the opinions of unqualified critics. We can always learn from the guidance of teachers, but the easily-garnered opinions of others are meaningless.

The Creative Block feeds on ego insecurity. And those insecurities come from a morbid concern for the opinion of others regarding the final "product". Remove the "product" focus of your attitude and your Creative Block becomes an anemic and hungry pauper.

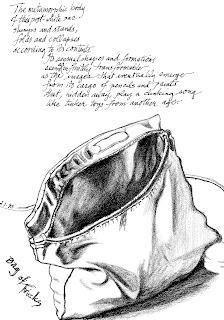

The drawing about is a study I did of the pouch in which I carried pencils, erasers, sharpeners, and sand blocks, the tools of my drawing practice. Once the drawing was finished I wrote that piece that you see above it, which reads as follows: The metamorphic body of this post-white sac slumps and stands, folds and collapses according to its contents. Its sensual shapes and formations seem as infinitely transformative as the images that eventually emerge from its cargo of pencils and paints that, hidden away, play a clinking song like tinker toys from another age.

The whole process of the drawing took me back, as the last line suggests, to my childhood, and it taught me that I'd been carrying around pouches of pencils all my life.

Whenever I come to a creative place that feels stuck, I interact with something at hand and make that thing the whole world. I challenge myself to make it my inspiration. It takes my mind off of the stuck place and keeps me working. The creative process from the distraction usually teaches me something to apply to my stuck place and before long I have kicked myself into gear again.

No comments:

Post a Comment